The Socio-Functional Theory of Human Nature

The Socio-Functional Theory of Human Nature

A theory about the Socio-Functional essence of human nature

Highlights:

-

-

- The evolutionary meaning (and purpose) of life

- The role of the common psychological human needs and their explanations

- The ultimate human selfishness

- The similarities and differences between people and our strengths

- Can a person change, and how

- The ultimate personal responsibility and luck – explained

- Applications in real life

-

Since the earliest times, we have always sought meaning.

Meaning of life and of our existence.

Meaning and answer to the question “Why?”.

Why do we suffer, why do we rejoice, why do we love, why do we feel this way or the other, why do we do the things we do, why others are the way they are, and many other such torments, all starting with the question “why?”

The truth is that as many people on earth are – as many opportunities to discover different meanings are there.

However, in order for any meaning to exist to anyone, this person must exist in the first place. To have been born as a result of the continuation of the species carried out by his parents.

The individual, however, rarely thinks about these questions.

We don’t think of ourselves as a biological species. Therefore, we often don’t see the continuation of the species as an evolutionary or biological task, but rather as a personal choice influenced by our understandings, and/or policies, trends, fashions, and biases.

In this line of thought, it is important to emphasize that our existence as a species is a precondition for any meaning to be sought afterward.

That being said, the first step is to reproduce.

This also brings us to the evolutionary goal of all biological species, to which we as people also belong: to reproduce and thus contribute to the survival of their species.

If we fail to achieve this goal, humanity will simply disappear from the face of the Earth.

That said, it becomes clear that at a deep biological level the “meaning of life” is the continuation of the species.

In other words, the deep underlying motive of all living things is the fulfillment of this evolutionary goal.

The world itself, with its natural characteristics, is a harsh place to live in.

To this, we add the fact that all species (including us) inhabit the same territory in which resources and space are limited and therefore have to coexist in constant competition for them.

But as we know, even though we are currently at the top of the food pyramid, we do not enjoy a very competitive physiology (compared to many animal species, our physical strength, teeth, claws, and senses, are uncompetitive, in the context of possible physical collision. We also don’t have tusks, venom, horns or spikes, etc. advantages that many species have).

All this puts us in front of constant challenges throughout our life, in our quest to achieve the evolutionary goal.

The number of these challenges is indeed huge, but they are often similar in type, origin, and characteristics.

This makes it easier for us to deal with them.

In reality, we do not have to deal with millions, but with several types, or in other words, groups of challenges with similar characteristics, origins, and types.

These groups of challenges could be classified and reduced logically (by similarities) to a few in number.

Our ability to deal with these few groups of challenges determines our ability to survive as a species.

This turns the need to “deal” with these groups of challenges into a major driving force – something that every person has to do everywhere and constantly, and without which survival becomes a significantly more difficult task.

For this reason, we view addressing each of these groups of challenges as a necessity, or in other words, a basic psychological need.

Thanks to millennia of development, evolution has equipped us with various mechanisms to deal with these sets of challenges, helping only the most adaptable of people to survive and continue to reproduce and pass on their genes over time.

We call these specific mechanisms “Human Nature”.

On the one hand, human nature is biologically conditioned by the biochemical processes in our bodies, but on the other hand, it is socially influenced, as we live in groups to more easily cope with the challenges of the environment.

This coexistence in groups requires some of the aforementioned coping mechanisms to be socially oriented.

For this reason, we call the mechanisms for dealing with challenges (and correspondingly satisfying the mentioned needs) “Socio-Functional” and we say that human nature is socio-functional in its essence.

In order to be able to build a qualitative understanding of what has been described so far, we will look at the mentioned groups of needs without ordering them in order of importance:

1. The need for gratification: As it became clear, the importance of satisfaction of our needs is so great that our survival as a species literally depends on it. However, how does a person know when a certain need of his has to be satisfied? In nature, there is a concept called “Homeostasis” – a constant striving of every system, (such as the human body) to maintain a balance between the internal and external environment of the system. Whenever homeostasis (balance) is disturbed, certain mechanisms are activated to drive various processes to restore this balance. We call this group of mechanisms “Gratification“.

2. The need for security: The harsh and unpredictable environment we live in, creates the need for a set of mechanisms to help us avoid anything risky and dangerous in order to protect ourselves from harm. We call this group of mechanisms “Caution“.

3. The need to be healthy: The presence of a variety of bacteria, germs, and other pathogens, as well as the presence of a variety of negative influences, including social ones (coming from the behavior of others), makes the environment threatening to our health in ways that often remain “hidden” for the mechanisms mentioned above (that deals with potential injuries). This threatens our health and gives rise to the need for a set of mechanisms to help us take care of it, avoiding these negative influences. We call this group of mechanisms “Well-Being“.

4. Need for predictability: The only sure thing in this world is change. It is constantly happening, it is unpredictable, and it brings with it challenges and risks. The more difficult it is for a person to adapt “on the fly” to changes, the greater the need for predictability and structure that person feels in order to more easily cope with the challenges that come with these changes. This gives rise to the need for a set of mechanisms to help us deal with change in one of two possible ways – either by improving our ability to adapt “on the fly” or by helping us to structure the world in such ways so that it is less chaotic and more predictable for us. We call this group of mechanisms “Adaptability”.

5. Need for stimulation: The ability to adapt to change, however, is related to the tendency of the human organism, once adapted, to get used to the circumstances and conditions in which it finds itself. This tendency is influenced by the already mentioned striving for “Homeostasis”. Homeostasis leads to a kind of stagnation for the person in the so-called “Comfort zone”. The changing nature of the world and environment, however, does not care for our quest for homeostasis. This gives rise to the need for a set of mechanisms to help us develop and thereby increase our ability to adapt to ever greater and more drastic changes and challenges. We call this group of mechanisms “Openness to experience“.

6. The need to identify the useful and good for our needs: In the process of pursuing the stimulation described above, we have the need to identify if we either encountered a useful or harmful phenomenon for our needs. This gives rise to the need for a set of mechanisms directing us to such ways of interacting with the surrounding world, which “indicate” to us whether what is happening (the thing with which we interact) is useful for our needs or not. We call this group of mechanisms “Enjoyment”.

7. The need to move towards the useful, the good, and the fruitful in the future: Our ability to identify the useful mentioned above leads us to another interesting phenomenon. We get the opportunity to predict those interactions which will potentially improve our ability to satisfy our needs. This, in turn, gives rise to the need for a set of mechanisms to help us move towards and eventually achieve these results in the future and thus improve our ability to satisfy our needs. We call this group of mechanisms “Ambition“.

8. Need for resources: Maintaining the previously mentioned homeostasis is related to the expenditure of energy, which is finite in the human body and is exhausted after a certain time (different for each individual). To be able to continue functioning, we need to manage the expenditure of our energy, as well as regenerate it. Thus, we store, redirect and prioritize its expenditure (until it is restored) only for the “most important” (subjectively) needs. Both the management of energy in the human body and its regeneration are processes related to various resources that we acquire from interaction with the environment. This gives rise to the need for a group of mechanisms to stimulate the acquisition, storage, and distribution of these resources, as well as the regeneration of energy following their absorption. We call this group of mechanisms “Thriftiness”.

9 Need for social status: As we mentioned at the beginning of the theory, resources are a finite number (for any given territory) and often there are not enough for everyone. This gives rise to the phenomenon of social hierarchy (the higher in this hierarchy we are, the more benefits we gain), and it gives rise to the need for mechanisms that will help us to position ourselves higher in this social hierarchy. Thus, we enjoy more privileges such as time, attention and resources, access to intimate partners, information, etc. – all in support of the satisfaction of our needs. We call this group of mechanisms “Status”.

10. The need to continue the species: As it became clear from the introductory part of the present theory, the continuation of the species is the main evolutionary goal of every living organism, including people. This gives rise to the need for a set of mechanisms to assist this process. We call this group of mechanisms “Intimacy”.

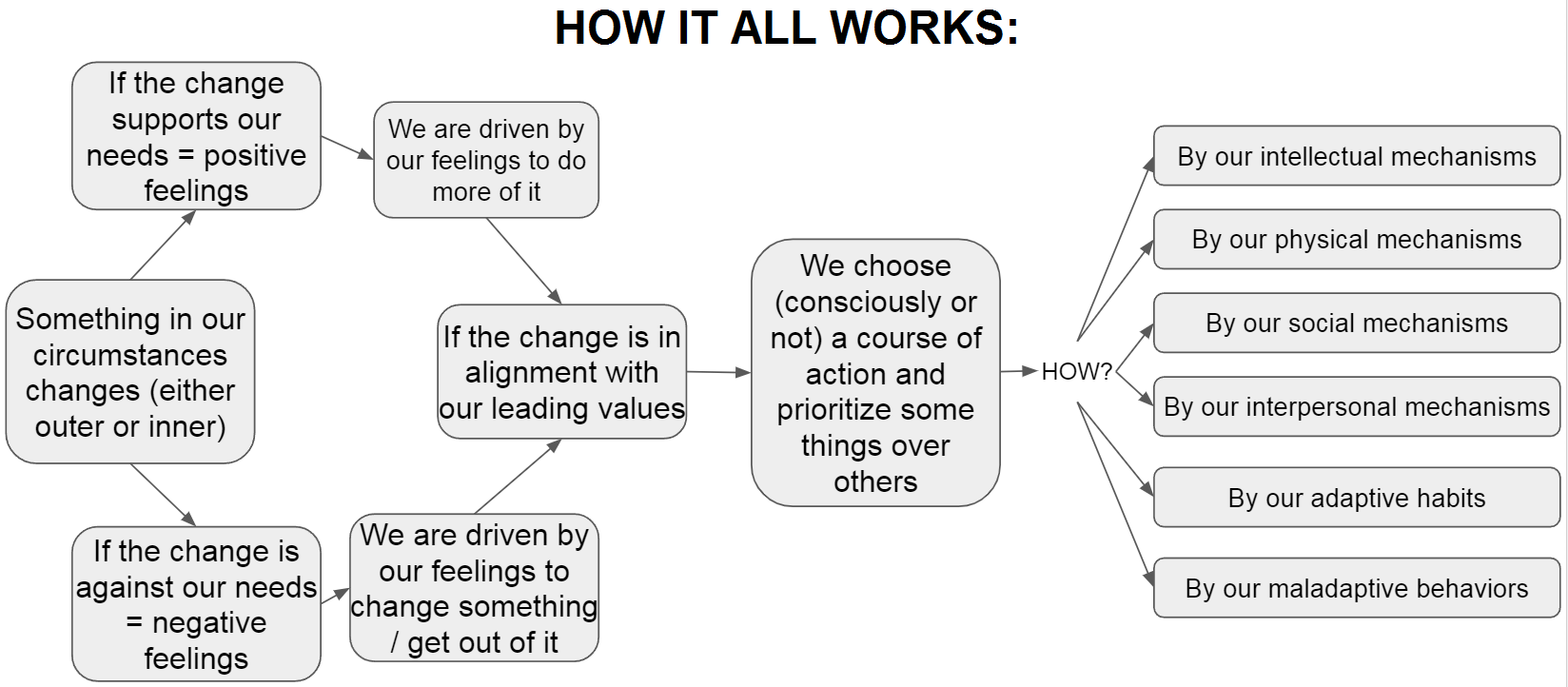

So far so good, you might say, but how does it all actually work?

What exactly are these mechanisms and how do they work in practice – in the real world?

In order for these so-called needs to be satisfied, nature has given us a few different ways to make this process happen. Here they are:

- Through feelings

- Through our intellect

- Through our body

- Through other people (functioning in a group)

- Through our interaction with another person (interpersonal interaction)

- Through our behaviors (adaptive and maladaptive)

- Through the choices we make

Since everything we do can be traced to these few “ways”, this makes them indistinguishable from the needs explained earlier. In other words – if we want to satisfy our needs, we need to use those ways, which basically turn them into needs themselves.

We call them “Secondary Needs”.

An important clarification is that just because they are called secondary does not mean they are less important than the primary described above. Often, people may experience these needs as even more important. It just goes to show that they serve to satisfy the basic ones from above.

Let’s look at them one by one:

11. Feelings (the need to distinguish between good and bad): Since we (like many other living things) are born, to put it mildly, unprepared for all the challenges that the world throws at us, we need a way to distinguish good from bad. Therefore, nature had to provide us with a mechanism that would allow us to orient ourselves on a purely intuitive level about what is useful and what is harmful to us and our needs. Thus, we experience positive feelings in relation to things that bring us closer to satisfying our needs and negative feelings in relation to things that move us away from satisfying them. We say that feelings have a “motivational character” because they move us towards the given thing or away from it (depending on whether or not it is useful for our needs or harmful to them).

12. Intellect (the need for awareness, understanding, and meaning): The feelings described above “push us around” according to the situation. This is often a too primitive and maladaptive way of dealing with challenges, as it encourages only the momentary gratification, “here and now”, of a particular need, without taking into account the role of the person in the context of different circumstances, past lessons, future possibilities and the interrelationships between phenomena. This gives rise to the need for a set of mechanisms that would give us the ability to process the flow of information coming through the senses as a result of our interaction with the surrounding world, as well as to store it for future use. This group of mechanisms makes possible for us the process of awareness and understanding of ourselves and our existence in the context of the surrounding world, its phenomena and the time frame of everything in existence. These mechanisms provide us with a measure of self-control and influence over our feelings and help us to more adaptively satisfy our needs in view of our own conditions, past, future, and the interrelationships between all the phenomena connected with them. It is these mechanisms that actually position humans at evolutionary higher levels compared to other animal species. And the group of mechanisms, we call “Intellect“.

13. Body (the need for effective interaction with the environment): Our non-competitive physique compared to other species, described at the beginning, requires nature to seek alternative means of compensation so as to give us a chance. These alternative methods should help us use our body more adaptively (instrumentally) and efficiently (conserving energy) and thus more successfully satisfy our needs. We call this group of mechanisms “Physical Efficiency“.

14. Through other people (the need to function in groups): As mentioned at the beginning, one of the ways we cope with challenges is by coming together and living in groups with other people to increase our chances of survival and satisfying our needs. Thus arises the need for a set of mechanisms to stimulate our ability to find groups, join them, and use them to satisfy our needs. We call this group of mechanisms “Sociability”.

15. Interpersonal interaction (the need to get along with other people): As it became clear from the previous need, in order to get support for satisfying our needs, we organize our lives in groups. But this, in itself, is a problem, since even within the group, resources are limited and not always enough for everyone. This leads to intragroup competition. It is, however, detrimental to the group itself and would lead to its collapse, as each member of the group would pursue his own interest. This gives rise to the need for a group of mechanisms that allow us to orient ourselves on a purely intuitive level about what in relationships with other people is useful and what is harmful, both for our personal needs and for those of others. Through these mechanisms, we acquire the ability to identify the needs of others and match our own with theirs, adapting. It even gives us an incentive to help other people in the process of meeting their needs. Without these mechanisms, groups simply could not exist and humans could not coexist together, let alone continue the species. We call this group of mechanisms “Interpersonal Sensitivity”.

16. Behaviors (adaptive) (the need for the group to accept us): To function successfully in a group, however, it is not enough for us to find a group and join it. The group, in turn, must also accept us. This gives rise to the need for a set of mechanisms to help us engage in such behaviors in the context of coexistence with other people that help us to be accepted by the group. We call this group of mechanisms “Adaptive Habits“.

17. Behaviours (maladaptive) (the need to satisfy our needs despite the group and other people): Living in a group, on the other hand, often leads to an unpleasant consequence – the group imposes on us certain patterns of behavior that are acceptable to it, but which are often harmful to our individual needs. And since we always prioritize our personal needs, this gives rise to the need for a set of mechanisms to help us satisfy our needs despite social expectations. We call this group of mechanisms “Socially Maladaptive Behaviors”.

18. The choices that we make (the need for the “right” environment and circumstances): The fact that we all grow up in different life circumstances and conditions, plus all the influences from family, social environment, media, cultural characteristics, etc., leads to the formation of the last – this time entirely social group of mechanisms for dealing with challenges. We call this group of mechanisms “Values” and it is a combination of certain beliefs, attitudes, and preferences in relation to what and how is good, useful, and valuable in the context of our needs.

The interesting thing about Values is that if a person finds himself in circumstances that are not in harmony with his values, he experiences negative feelings. Accordingly, in the opposite scenario, he experiences positive ones. This automatically means that we all need to put ourselves in the “right” circumstances (places, activities, social environment, partners, etc.) that are in tune with our values if we want to lead a satisfactory life.

As you may have noticed, the list of secondary needs above continues the numbering from the primary ones. The information is structured in this way because for a person, the way of “experiencing” primary and secondary needs is very similar. Or in other words, we do not feel the two types of needs differently. Moreover, failure to satisfy both types of needs has lasting negative consequences for both – our physical and mental health.

For this reason, we say that if a person permanently neglects his needs (in general – both types), then he will not be able to function normally and at some point, this will lead to a deterioration of his health.

And this brings us to the ultimate human selfishness, the explanation of ego and self-interest…

We can summarize that the 18 needs (basic + secondary) described above, are the driving force behind everything in our lives. In other words, everything we do, think, choose, and say in our lives is the result of one or more of the described needs.

This is also the reason for the notion that human beings are inherently selfish and that we all act to satisfy our own needs. Even when we think and act for the benefit of another person, the ultimate goal is still to satisfy one or more of our own needs.

What all people have in common is that each person possesses all of the mentioned mechanisms (serving to satisfy needs). Therefore, we often refer to these mechanisms as characteristics of human nature.

And this is no accident. As has become clear, if we do not satisfy these needs, we will not survive as a species.

This is important for one more reason – it is good to understand that our needs should come first.

Why?

Because we won’t be able to fully take care of anyone else if we haven’t taken care of ourselves first!

Sounds counter-intuitive right?

Consider the following puzzle:

Imagine you are in a crashed plane. Everything burns. There are you, a mother with a small child, and an elderly person on the plane. Everyone but you is stuck without being able to move. There is only one wet blanket available that you could use to protect someone.

Who will you use the blanket for?

The correct answer is – for you. And this is not accidental… All participants in the example will have a greater chance of survival if you save yourself with the blanket and go to seek help. Otherwise, no matter whom you save, you all die – remember, they’re stuck!

And while this is an imaginary scenario, we can easily think of real-life examples. Here are a few:

- A mother could not fully care for her child if her needs were not met (at least to some extent). Otherwise, she becomes irritable, short-tempered, neglectful and unreasonable. It focuses on the wrong things and misses important details in the context of child care.

- A husband could not take care of his wife if his needs were not met (at least to some extent). Otherwise, he too, like the above example, will feel, think and act against her instead of for her.

- A leader in an organization could not take care of the needs of the organization if his needs were not met (at least to some extent). Otherwise, he will look for ways to extract maximum benefits for himself, which will lead to the neglect of organizational processes, and hence lead to a decrease in the effectiveness of the organization.

All this comes to show the profound misunderstanding in the modern world of the importance of healthy selfishness.

That said, it’s important to clarify what healthy selfishness means. Selfishness should never come “at the expense” of other people. Or in other words – one should always prioritize one’s own needs, BUT without preventing others from doing the same or harming other people’s needs.

Ok, but why are people different you ask? And why are some people more clearly expressed, egoists than others?

This is how we get to the idea of the similarities and differences between people…

What all people have in common is that each person possesses all of the mentioned mechanisms (serving to satisfy needs).

Therefore, we often call these mechanisms universal characteristics of human nature.

Differences between people, in turn, are due to the degree and strength with which each of these characteristics manifests itself in each individual.

We can think of this “manifestation” as a scale from 1% to 100%. The closer the individual’s score is to 1%, the less pronounced the specific characteristic is. Conversely, the closer it is to 100%, the more strongly it is manifested.

As it became clear above, the mentioned characteristics are actually the socio-functional mechanisms that we use to satisfy our needs.

Therefore, the higher the scores on all mechanisms for satisfying a given need, the more capable we are of satisfying it, and the more time, attention, energy, and resources we will devote to satisfying it.

Why do we care?

Very simply – the more time, attention, energy, and resources we devote to satisfying a given need, the less we have left for other needs.

At some point, this makes us “good” at satisfying some needs at the expense of others. or in other words, it builds in us “strengths” for certain things and “weaknesses” for others.

An important understanding of “strengths” and “weaknesses” is that they are not “good” or “bad” on their own.

They are only so in a certain context.

To illustrate what has been said, we will give an example:

One of the mechanisms from the group of “Goal–orientedness” (for satisfying the need to move towards the useful in the future) is called “Energy”. High scores on the scale (trait) “Energy” (describing a person’s tendency to be active, energetic, and to think, act, and generally function “at a higher speed” than other people) would be useful for a person who deals with sports, for example.

On the other hand, the same high scores on the scale in question would not be of such importance for a person working as a watchmaker, for example.

Thus, we arrive at the logical question of how a person can objectively assess what his results are for each of the individual characteristics (how strong are the manifestations of the individual mechanisms specifically for him) and, accordingly, what would he be best at according to his profile.

And the answer is: through individual psychological profiling. (You can learn more about this here)

This raises a significant question: Can a person change?

An important topic that we should touch on is the question of whether all these characteristics that we have mentioned and that we can “measure” through psychological profiling are permanent over time, or can a person develop and change?

There is no simple answer…

Although human nature is lasting (durable) and hard to change, there are scenarios where it can change over time. Here they are:

- If a person suffers a serious trauma (for example, a serious accident or physical injury) capable of permanently changing the internal biochemistry of his body and/or lifestyle.

- If a person drastically changes the environment in which he lives. For example, after a secluded life on a livestock farm in Africa, to move to a large, cold northern city in Finland, where his daily life is connected with sales and constant contact with many people.

- If, for some reason, biochemical, and genetic processes or diseases are triggered in his body, which significantly changes its neuro-biochemical structure.

- If a person undergoes psychotherapy or another intensive process of working with professionals in the context of his personality.

- If a person (for one reason or another) permanently fails to satisfy any of the previously described needs for long periods of time (years).

To summarise, it is good to understand that change in human nature is possible, but it is difficult, slow, and often not very drastic.

This suggests that an important step in a person’s life is to seek a fit between his human nature and the demands of the environment. If we think about it, since it is difficult for a person to change, if he wants to be successful, satisfied, and happy in life, it makes much more sense to strive to find jobs, long-term intimate partners, hobbies, etc., that are in harmony with his characteristics, instead of ones that require radically different traits (See the example of tempo-rhythm above).

The ultimate personal responsibility and luck – explained

The already-established understanding of the Socio-Functional essence of human nature informs us about what makes us do the things we do.

In fact, summing up the influence of all the constructs and mechanisms described above, we can claim that they are responsible for more than 99% of everything we do, think, choose, speak, and believe.

This is an extremely important finding, as it helps us to realize that for every outcome in our life, everything that happens to us (or at least 99% of it) is actually due to ourselves.

To test this thesis, we can try to analyze our previous experiences, which will lead us to the conclusion that there is no event in our life that cannot be traced back in time to something we said, did, decided, or thought of. (or respectively something that we did NOT say, do, decided, or thought)

This practically means that at the end of the day, we are fully responsible for everything in our lives!

In order to address the obvious question – “And where does the other 1% go?” – the Socio-Functional Theory examines the concept of “Luck” in the context of the already described human characteristics:

Luck is those events, circumstances, and phenomena for which objectively there was no information that a person could receive, understand and use in advance in order to influence the events.

It is important to clarify that if such information existed, but the person for one reason or another did not capture, process, and use it, then we are no longer talking about luck, but about the inability to cope, which automatically turns it into a personal responsibility again.

With this, the Socio-Functional Theory exhausts the cause-and-effect relationships for everything in human life.

From here on, the question follows: “What do we do with this knowledge?

Since knowledge is only meaningful and useful in the context of its real-world applicability, to conclude, we will focus on the 6 areas that matter most to us as humans and to the quality of our lives.

We say that these areas of life matter most because they often take up most of our time, effort, resources, and awareness.

In addition, the things we do in these 6 areas of our life largely determine its quality.

Making an effort to improve any one of those 6 areas has a lasting, holistic, positive impact on each of the other 5, thus each contributing to our overall happiness, satisfaction, and meaning in our lives.

The Socio-Functional Theory of Human Nature describes the six most important areas of human life as follows:

- Relationships, Intimacy, and Love

- Parenthood

- Health

- Career, Business, and Leadership

- Social contacts and Reputation

- Personal development

And since the reason we created this theory and our main mission is to help people live happy, meaningful, and fulfilling lives, we offer you just that – to help you master the ability to apply this knowledge in the 6 main areas of life, in order to improve it in each of them.

Find out more about the applicability of Socio-Functional Theory and the problems it solves – here…

And if you want to learn more about your human nature and its manifestations in any of the 6 areas described, we offer you the process of in-depth psychological profiling, which aims to shed light on the characteristics of your human nature described in the theory, and the ways in which these characteristics influence of your life…

The Socio-Functional Theory was created after an in-depth meta-analysis of the last 100 years of psychological literature and its cross-reference with the most recent discoveries in the fields of neurobiology, social psychology, and the field of psychometrics. Here is an extensive reference list:

- “The Evolutionary Psychology of Human Motivation” by David M. Buss, Psychological Inquiry, 2002

- “The Psychological Needs that Motivate Human Behavior” by Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan, American Psychologist, 2000

- “The Evolutionary Basis of Personality Traits” by David Sloan Wilson and Elliott Sober, Personality and Social Psychology Review, 1994

- “The Evolution of Character” by David Sloan Wilson, Biological Theory, 2009

- “The Role of Temperament and Character in Personality” by Antonio Terracciano et al., Journal of Personality, 2005

- “Core Values and Personal History: Their Role in Personality Development” by Dan P. McAdams and Jennifer L. Pals, Journal of Research in Personality, 2006

- “The Role of Habits in Personality” by Wendy Wood and David Neal, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2009

- “Defense Mechanisms in Evolutionary Perspective” by David Sloan Wilson and Elliot Sober, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1994

- “The Role of Psychological Needs in the Development of Personality: A Russian Perspective” by Irina Trifonova, Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 2013

- “The Role of Habits in the Development of Personality: A Russian Perspective” by Irina Trifonova, Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 2018

- “Defense Mechanisms in the Russian Psychological Tradition” by Irina Trifonova, Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 2019

- “The Essence of Human Nature in the Perspective of Robert Hogan’s Model of Personality” by Ana Froid and Robert Hogan, Journal of Personality, 2015

- “The Role of Defense Mechanisms in Personality: A Perspective from the Hogan Personality Inventory” by Robert Hogan and Robert B. Kaiser, Journal of Research in Personality, 2005

- “The Evolutionary Purpose of Personality: An Analysis Using the Hogan Development Survey” by Robert Hogan and Robert B. Kaiser, Journal of Research in Personality, 2008

- “The Relationship Between Psychological Needs and Personality: An Analysis Using the Anna Freud Measure of Personality Styles” by Robert Hogan and Robert B. Kaiser, Journal of Research in Personality, 2010

- “The Relationship Between Temperament and Character in Personality: An Analysis Using the Anna Freud Measure of Personality Styles” by Robert Hogan and Robert B. Kaiser, Journal of Research in Personality, 2012

- “The Role of Core Values in Personality: An Analysis Using the Anna Freud Measure of Personality Styles” by Robert Hogan and Robert B. Kaiser, Journal of Research in Personality, 2014

- “The Social Psychology of Personality” by Mark R. Leary and June Price Tangney, Handbook of Social Psychology, 2010

- “The Role of Psychological Needs in Social Behavior” by Roy F. Baumeister and Mark R. Leary, Psychological Bulletin, 1995

- “Temperament, Character, and Social Interaction” by Theodore Millon and Roger D. Davis, Handbook of Interpersonal Psychology, 2007

- “Core Values in Social Psychology” by David Sloan Wilson, Social Psychology Quarterly, 2008

- “Habits in Social Psychology” by Wendy Wood and David T. Neal, Annual Review of Psychology, 2009

- “Defense Mechanisms in Social Psychology” by Susan T. Fiske, Annual Review of Psychology, 2002

- “An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values” by Shalom H. Schwartz, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2012

- “Basic Individual Values, Gender, and Culture” by Shalom H. Schwartz and Qi Wang, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 2011

- “The Hierarchy of Needs: A Theory of Human Motivation” by Abraham Maslow, Psychological Review, 1943

- “Self-actualization and Psychological Health” by Abraham Maslow, Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 1971

- “The Farther Reaches of Human Nature” by Abraham Maslow, Viking Press, 1971

- “Values and Value Orientations in the Theory of Action: An Overview” by Shalom H. Schwartz, in “Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 20” edited by Mark P. Zanna, Academic Press, 1988

- “12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos” by Jordan Peterson, Random House Canada, 2018

- “Personality and Its Transformations” by Jordan Peterson, Self-published, 2018

- “The Emotional Foundations of Personality: A Neurobiological and Evolutionary Theory” by Jaak Panksepp, Journal of Research in Personality, 2004

- “Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions” by Jaak Panksepp, Oxford University Press, 1998

- “The Basic Emotional Circuits of Mammalian Brains: Do Animals have Affective Lives?” by Jaak Panksepp, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 2004

- “The Biological Basis of Personality Traits” by Jaak Panksepp and Lucy Biven, W.W. Norton & Company, 2012

- “The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis” by B.F. Skinner, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1938

- “Science and Human Behavior” by B.F. Skinner, Macmillan, 1953

- Buss, D. M. (1994). The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating. Basic Books.

- Buss, D. M. (2000). The Dangerous Passion: Why Jealousy Is as Necessary as Love and Sex. Free Press.

- Buss, D. M. (1999). Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind. Allyn & Bacon

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. Guilford Press.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 11(1), 54-67.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

- Wilson, D. S., & Sober, E. (1998). Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior. Harvard University press

- Wilson, D. S., & Sober, E. (1990). Evolution, Population Thinking, and Essentialism. Psychological Inquiry, 1(2), 131-145.

- Wilson, D. S., & Sober, E. (2010). Reintroducing Group Selection to the Human Behavioral Sciences. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(4), 315-327.

- Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R., Segal, N. L., & Costa, P. T. (2005). Personality Traits and the Regulation of Emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4), 709-722.

- Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R., Segal, N. L., & Costa, P. T. (2005). Personality and the Prediction of Exceptional Performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4), 703-709.

- Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R., Segal, N. L., & Costa, P. T. (2005). Age-Related Differences in Personality Traits Across the Adult Life Span: Evidence from Self-Reports and Observer Ratings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(1), 102-111.

- McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2006). The Person: An Introduction to the Science of Personality Psychology. John Wiley & Sons.

- McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2006). A Person-Centered Approach to Personality Psychology. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 327-342.

- McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2006). The Psychological Construction of the Life Story. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 2, 541-567.

- Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2009). Habits in Everyday Life: Thought, Emotion, and Action. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(4), 198-202.

- Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2010). Habits, Goals, and Identity. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(5), 356-366.

- Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2011). Habits: A Repeat Performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 198-202.

- Fiske, S. T. (2017). Social Cognition: From Brains to Culture. Sage Publications.

- Fiske, S. T. (2018). Social Beings: A Core Motives Approach to Social Psychology. John Wiley & Sons.

- Fiske, S. T. (2012). The Human Brand: How We Relate to People, Products, and Companies. John Wiley & Sons.

- Trifonova, I. (2010). Adaptability and personality structure in the Russian psychological tradition. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 48(1), 5-22.

- Trifonova, I. (2012). The concept of adaptability in the work of Alexander Rusalov. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 50(4), 7-26.

- Trifonova, I. (2014). Adaptability and personality development in the works of Alexander Luria. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 52(6), 1-20.

- Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2005). Personality and the Fate of Organizations. American Psychologist, 60(7), 681-696.

- Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2008). Personality and Adaptability: An Organizational Perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1201-1214.

- Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2010). The Role of Personality in Adaptability and Learning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(3), 553-566.

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and Personality. Harper & Row.

- Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a Psychology of Being. Van Nostrand.

- Maslow, A. H. (1971). The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. Viking Press.

- Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press.

- Panksepp, J. (2004). The Basic Emotional Circuits of Mammalian Brains: Do Animals Have Affective Lives? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 28(3), 365-384.

- Panksepp, J. (2004). The Emotional Foundations of Personality: A Neurobiological and Evolutionary Theory. In: D. J. Munz, D. J. Munz (eds.) Handbook of Personality Psychology. Elsevier, pp. 797-828.

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond Freedom and Dignity. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior. Macmillan.

- Leary, M. R., & Tangney, J. P. (2010). The Social Psychology of Personality. Guilford Press.

- Leary, M. R., & Tangney, J. P. (2003). Handbook of Self and Identity. Guilford Press.

- Leary, M. R., & Tangney, J. P. (2010). Self-Presentation: Impression Management and Interpersonal Behavior. In: M. R. Leary, J. P. Tangney (eds.) Handbook of Self and Identity. Guilford Press, pp. 541-568.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The Social Psychology of Emotion. John Wiley & Sons.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (2017). The Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications. Guilford Press.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (2005). The Cultural Animal: Human Nature, Meaning, and Social Life. Oxford University Press.

- Millon, T., & Davis, R. D. (2000). Personality Disorders in Modern Life. John Wiley & Sons.

- Millon, T., & Davis, R. D. (2003). Millon’s Clinical Personality Assessment. Oxford University Press.

- Millon, T., & Davis, R. D. (2007). Handbook of Interpersonal Psychology: Theory, Research, Assessment, and Therapeutic Interventions. John Wiley & Sons.

- Wilson, D. S. (2009). The Evolution of Character. Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, D. S. (2007). Evolution for Everyone: How Darwin’s Theory Can Change the Way We Think About Our Lives. Bantam Dell.

- Wilson, D. S. (2011). The Neighborhood Project: Using Evolution to Improve My City, One Block at a Time. Little, Brown and Company.

- Schwartz, S. H. (2012). Values and Culture. Cambridge University Press.

- Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1).

- Schwartz, S. H. (1988). Values and Value Orientations in the Theory of Action: An Overview. In: P. J. D. Drenth, H. Thierry, C. J. H. M. Hagendoorn (eds.) Advances in intergroup research. Elsevier, pp. 1-65.

- Peterson, J. (2018). 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Random House.

- Peterson, J. (2018). Personality and Its Transformations. Self-published.

- Peterson, J. (1999). Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief. Routledge.

- Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press.

- Panksepp, J. (2004). The Basic Emotional Circuits of Mammalian Brains: Do Animals Have Affective Lives? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 28(3), 365-384.

- Panksepp, J. (2004). The Emotional Foundations of Personality: A Neurobiological and Evolutionary Theory. In: D. J. Munz, D. J. Munz (eds.) Handbook of Personality Psychology. Elsevier, pp. 797-828.

- “Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011

- “Mindset: The New Psychology of Success” by Carol Dweck, Random House, 2006

- “Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment” by Martin Seligman, Free Press, 2002

- “The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature” by Steven Pinker, Penguin, 2002

- “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience” by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Harper Perennial, 2008

- “Emotions Revealed: Recognizing Faces and Feelings to Improve Communication and Emotional Life” by Paul Ekman, Owl Books, 2004

- “Self-Presentation: Impression Management and Interpersonal Behavior” by Mark R. Leary, Westview Press, 2004

- “Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy” by David D. Burns, Avon Books, 1980

- “Emotional Agility: Get Unstuck, Embrace Change, and Thrive in Work and Life” by Susan David, Avery, 2016

- “The Compassionate Mind” by Paul Gilbert, Constable, 2009

- “Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain” by Antonio Damasio, Penguin, 2005

- “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” by Oliver Sacks, Touchstone, 1985

- “The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present” by Eric Kandel, Random House, 2012

- “Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind” by V.S. Ramachandran, Quill, 1999

- “The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are” by Daniel J. Siegel, Guilford Press, 1999

- “Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers” by Robert Sapolsky, W.H. Freeman, 1994

- “Chemical Imbalance: A Neuroscientist’s Journey Through Mental Illness” by Steven E. Hyman, Harvard University Press, 2019

- “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion” by Jonathan Haidt, Vintage, 2012

- “The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk, Viking, 2014

- “How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain” by Lisa Barrett, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017

- “Forty-Four Juvenile Thieves: Their Characters and Home-Life” (1944) by John Bowlby

- “Maternal Care and Mental Health” (1951-1952) by John Bowlby

- “Child Care and the Growth of Love” (1953) by John Bowlby

- “Separation: Anxiety and Anger” (1953) by John Bowlby

- “Grief and Mourning in Infancy and Early Childhood” (1961) by John Bowlby

- “Childhood and Society” (1969) by John Bowlby

- “Attachment” (1969) by John Bowlby

- “A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development” (1988) by John Bowlby

- “Personality in Adulthood” by Robert R. McCrae and Paul T. Costa Jr, Guilford Press, 1999

- “The Five Factor Model of Personality” by Paul T. Costa Jr and Robert R. McCrae, Guilford Press, 1992

- “The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI)” by Paul T. Costa Jr and Robert R. McCrae, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1992

- “The Marshmallow Test: Understanding Self-Control” by Walter Mischel, Little, Brown and Company, 2014

- “Personality and Assessment” by Walter Mischel, John Wiley & Sons, 1968

- “Self-regulation in the service of goals” by Walter Mischel, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 50, 1999

- “Personality and Individual Differences: A Natural Science Approach” by Hans Eysenck, Plenum Press, 1995

- “The Structure of Human Personality” by Hans J. Eysenck, Routledge, 2003

- “Genetics, Intelligence and Education” by Hans Eysenck, Routledge, 1997

- “Personality: A Psychological Interpretation” by Gordon W. Allport, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1937

- “The Nature of Prejudice” by Gordon Allport, Addison-Wesley, 1954

- “Becoming: Basic Considerations for a Psychology of Personality” by Gordon Allport, Yale University Press, 1955

- “Identity: Youth and Crisis” by Erik H. Erikson, W.W. Norton & Company, 1968

- “Childhood and Society” by Erik H. Erikson, W.W. Norton & Company, 1950

- “The Life Cycle Completed (Extended Version)” by Erik H. Erikson, W.W. Norton & Company, 1982

- “Personality and Mood by Questionnaire” by Raymond B. Cattell, Jossey-Bass, 1971

- “Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology” by Raymond B. Cattell, Plenum Press, 1978

- “Personality and Motivation Structure and Measurement” by Raymond B. Cattell, World Book Company, 1950

- “General Intelligence, Objectively Determined and Measured” by Charles Spearman, American Journal of Psychology, 1904

- “The Nature of ‘Intelligence’ and the Principles of Cognition” by Charles Spearman, London: Macmillan, 1923

- “The Abilities of Man: Their Nature and Measurement” by Charles Spearman, New York: Macmillan, 1927

- “The Measurement of Adult Intelligence” by David Wechsler, Williams & Wilkins, 1939

- “Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children” by David Wechsler, The Psychological Corporation, 1949

- “Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale” by David Wechsler, The Psychological Corporation, 1955

- “Primary Mental Abilities” by Louis L. Thurstone, Psychometric Monographs, No. 1, 1938

- “Multiple Factor Analysis” by Louis L. Thurstone, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1947

- “The Vectors of Mind” by Louis L. Thurstone, Psychological Review, Vol. 45, 1938

- “The Measurement of Intelligence” by Robert M. Yerkes, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1921

- “The Army Mental Tests” by Robert M. Yerkes, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1921

- “The Intelligence of School Children: How Children Differ in Ability and What Can be Done for Them” by Robert M. Yerkes, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1926

- “The Nature of Human Intelligence” by J.P Guilford, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967

- “The Structure of Intellect” by J.P Guilford, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 56, 1959

- “Creativity” by J.P Guilford, American Psychologist, Vol. 5, 1950

- “Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences” by Howard Gardner, Basic Books, 1983

- “Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons” by Howard Gardner, Basic Books, 2006

- “Creating Minds: An Anatomy of Creativity Seen Through the Lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Gandhi” by Howard Gardner, Basic Books, 2011

- “Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity Synthesized” by Robert J. Sternberg, Cambridge University Press, 2003

- “Successful Intelligence: How Practical and Creative Intelligence Determine Success in Life” by Robert J. Sternberg, Plume, 1997

- “The Triarchic Mind: A New Theory of Human Intelligence” by Robert J. Sternberg, Viking, 1988

- “The g Factor: The Science of Mental Ability” by Arthur R. Jensen, Praeger, 1998

- “Bias in Mental Testing” by Arthur R. Jensen, Free Press, 1980

- “Race, IQ and Jensen” by Arthur R. Jensen, Routledge, 1985

- “Attachment and Loss: Vol.3. Loss, Sadness and Depression” by John Bowlby, Basic Books, 1980

- “The Nature of Love” by Harry Harlow, American Psychologist, Vol. 13, 1958

- “Maternal behavior of rhesus monkeys” by Harry Harlow and Margaret Kuenne Harlow, in: Physiology of Behavior, 1957

- “Love in Infant Monkeys” by Harry Harlow, Scientific American, Vol. 200, 1959

- “The Anatomy of Love: The Natural History of Monogamy, Adultery, and Divorce” by Helen Fisher, W.W. Norton & Company, 1992

- “Why Him? Why Her?: Finding Real Love by Understanding Your Personality Type” by Helen Fisher, Henry Holt and Company, 2009

- “The First Sex: The Natural Talents of Women and How They are Changing the World” by Helen Fisher, Random House, 1999

- “Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love” by Dorothy Tennov, Stein and Day Publishers, 1979

- “Psychology of Love” by Dorothy Tennov, Yale University Press, 1998

- “Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love” by Dorothy Tennov, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009

- “Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love” by Dr. Sue Johnson, Little, Brown and Company, 2008

- “Love Sense: The Revolutionary New Science of Romantic Relationships” by Dr. Sue Johnson, Little, Brown and Company, 2013

- “The Practice of Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy: Creating Connection” by Dr. Sue Johnson, Routledge, 2013

- “A triangular theory of love” by Robert J. Sternberg, Psychological Review, Vol. 93, 1986

- “The New Psychology of Love” by Robert J. Sternberg, Yale University Press, 2006

- “The Triarchic Mind: A New Theory of Human Intelligence” by Robert J. Sternberg, Viking, 1988

- “The Experimental Generation of Interpersonal Closeness: A Procedure and Some Preliminary Findings” by Arthur Aron, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 23, 1997

- “Self-Expansion as a Basic Motive for Social Interaction” by Arthur Aron, in: Handbook of Personal Relationships: Theory, Research, and Interventions, Chichester, UK: Wiley, 2011

- “The Relationship Closeness Inventory: Assessing the closeness of interpersonal relationships” by Arthur Aron, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, Vol. 21, 2004

- “Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model” by Caryl Rusbult, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 16, 1980

- “The Investment Model Scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size” by Caryl Rusbult, in: Commitment in romantic relationships, edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and Steven W. Rholes, New York: Guilford Press, 2014

- “The role of commitment in the development and maintenance of long-term relationships” by Caryl Rusbult, in: Advances in personal relationships: Commitment in romantic relationships, edited by Warren H. Jones and Daphne L. Finkel, Psychology Press, 2011

- “The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work” by John Gottman, Crown Publishers, 1999

- “What Predicts Divorce: The Relationship Between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes” by John Gottman, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1994

- “The Science of Trust: Emotional Attunement for Couples” by John Gottman, W. W. Norton & Company, 2011

- “Social relationships and health” by Sheldon Cohen, American Psychologist, Vol. 54, 1999

- “The role of social support in the stress process” by Sheldon Cohen, in: Social Support: An interactional view, edited by Sheldon Cohen and Samuel Leonard, John Wiley & Sons, 1985

- “Social support and physical health” by Sheldon Cohen, in: Handbook of Health Psychology, edited by Andrew Baum, Sheldon Cohen and Ronald Kessler, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001

- “The All-or-Nothing Marriage: How the Best Marriages Work” by Eli J. Finkel, Penguin Press, 2017

- “Self-regulation in close relationships” by Eli J. Finkel and Caryl Rusbult, in: Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, research, and interventions, edited by Steve Duck and David Perlman, John Wiley & Sons, 1992

- “The psychology of close relationships” by Eli J. Finkel, in: Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 65, 2014

- “Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ” by Daniel Goleman, Bantam Books, 1995

- “Working with Emotional Intelligence” by Daniel Goleman, Bantam Books, 1998

- “Leadership That Gets Results” by Daniel Goleman, Harvard Business Review, 2000

- “Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice” by Howard Gardner, Basic Books, 1993

- “Creating Minds: An Anatomy of Creativity Seen Through the Lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Gandhi” by Howard Gardner, Basic Books, 2011

- “The Unschooled Mind: How Children Think and How Schools Should Teach” by Howard Gardner, Basic Books, 1991

- “In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life” by Robert Kegan, Harvard University Press, 1994

- “The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development” by Robert Kegan, Harvard University Press, 1982

- “An Everyone Culture: Becoming a Deliberately Developmental Organization” by Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey, Harvard Business Review Press, 2016

- “Mindset: The New Psychology of Success” by Carol Dweck, Random House, 2006

- “Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development” by Carol Dweck, Psychology Press, 1999

- “Can Personality Be Changed?” by Carol Dweck, Scientific American, Vol. 301, 2009

- “On Becoming a Leader” by Warren Bennis, Basic Books, 1989

- “Leaders: The Strategies for Taking Charge” by Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus, Harper & Row, 1985

- “The Leadership Moment: Nine True Stories of Triumph and Disaster and Their Lessons for Us All” by Michael Useem and Warren Bennis, Three Rivers Press, 1999

- “The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done” by Peter Drucker, HarperBusiness, 2006

- “Managing Oneself” by Peter Drucker, Harvard Business Review, 1999

- “The Practice of Management” by Peter Drucker, HarperBusiness, 1954

- “Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don’t” by Jim Collins, HarperBusiness, 2001

- “Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies” by Jim Collins and Jerry I. Porras, HarperBusiness, 1994

- “How the Mighty Fall: And Why Some Companies Never Give In” by Jim Collins, HarperBusiness, 2009

- “The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail” by Clayton Christensen, Harvard Business Review Press, 1997

- “Seeing What’s Next: Using Theories of Innovation to Predict Industry Change” by Clayton Christensen, Scott D. Anthony, and Erik A. Roth, Harvard Business Review Press, 2004

- “Competing Against Luck: The Story of Innovation and Customer Choice” by Clayton Christensen, Taddy Hall, Karen Dillon, and David S. Duncan, HarperBusiness, 2016

- “Developmental sequence in small groups” by Bruce Tuckman, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 63, 1965

- “Tuckman’s stages of group development” in: The Oxford Handbook of Group Psychology, edited by Michael Hogg and Joel Cooper, Oxford University Press, 2012

- “Stages of small-group development revisited” by Bruce Tuckman, Group and Organizational Management, Vol. 2, 1977

- “Organizational Culture and Leadership” by Edgar Schein, John Wiley & Sons, 2004

- “Career Anchors: Discovering Your Real Values” by Edgar Schein, Pfeiffer, 2009

- “Culture: The Missing Concept in Organization Studies” by Edgar Schein, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 48, 2003